What Is The Relationship Between Nominal Money Supply And The Price Level In The Long Run

22.2 Aggregate Demand and Aggregate Supply: The Long Run and the Curt Run

Learning Objectives

- Distinguish betwixt the short run and the long run, as these terms are used in macroeconomics.

- Draw a hypothetical long-run amass supply curve and explain what it shows almost the natural levels of employment and output at diverse price levels, given changes in aggregate need.

- Describe a hypothetical curt-run amass supply curve, explicate why it slopes up, and explain why it may shift; that is, distinguish between a modify in the aggregate quantity of goods and services supplied and a change in brusque-run aggregate supply.

- Discuss various explanations for wage and price stickiness.

- Explain and illustrate what is meant by equilibrium in the short run and relate the equilibrium to potential output.

In macroeconomics, we seek to empathise two types of equilibria, one corresponding to the short run and the other corresponding to the long run. The short run in macroeconomic analysis is a menstruation in which wages and another prices do not respond to changes in economic conditions. In sure markets, every bit economical conditions change, prices (including wages) may not adapt speedily plenty to maintain equilibrium in these markets. A sticky price is a cost that is tedious to adjust to its equilibrium level, creating sustained periods of shortage or surplus. Wage and price stickiness prevent the economic system from achieving its natural level of employment and its potential output. In dissimilarity, the long run in macroeconomic assay is a period in which wages and prices are flexible. In the long run, employment will move to its natural level and real Gdp to potential.

We begin with a discussion of long-run macroeconomic equilibrium, because this blazon of equilibrium allows usa to run across the macroeconomy subsequently total market adjustment has been achieved. In contrast, in the curt run, price or wage stickiness is an obstruction to full aligning. Why these deviations from the potential level of output occur and what the implications are for the macroeconomy will be discussed in the section on short-run macroeconomic equilibrium.

The Long Run

As explained in a previous chapter, the natural level of employment occurs where the real wage adjusts so that the quantity of labor demanded equals the quantity of labor supplied. When the economy achieves its natural level of employment, it achieves its potential level of output. We will run into that real GDP eventually moves to potential, because all wages and prices are assumed to be flexible in the long run.

Long-Run Aggregate Supply

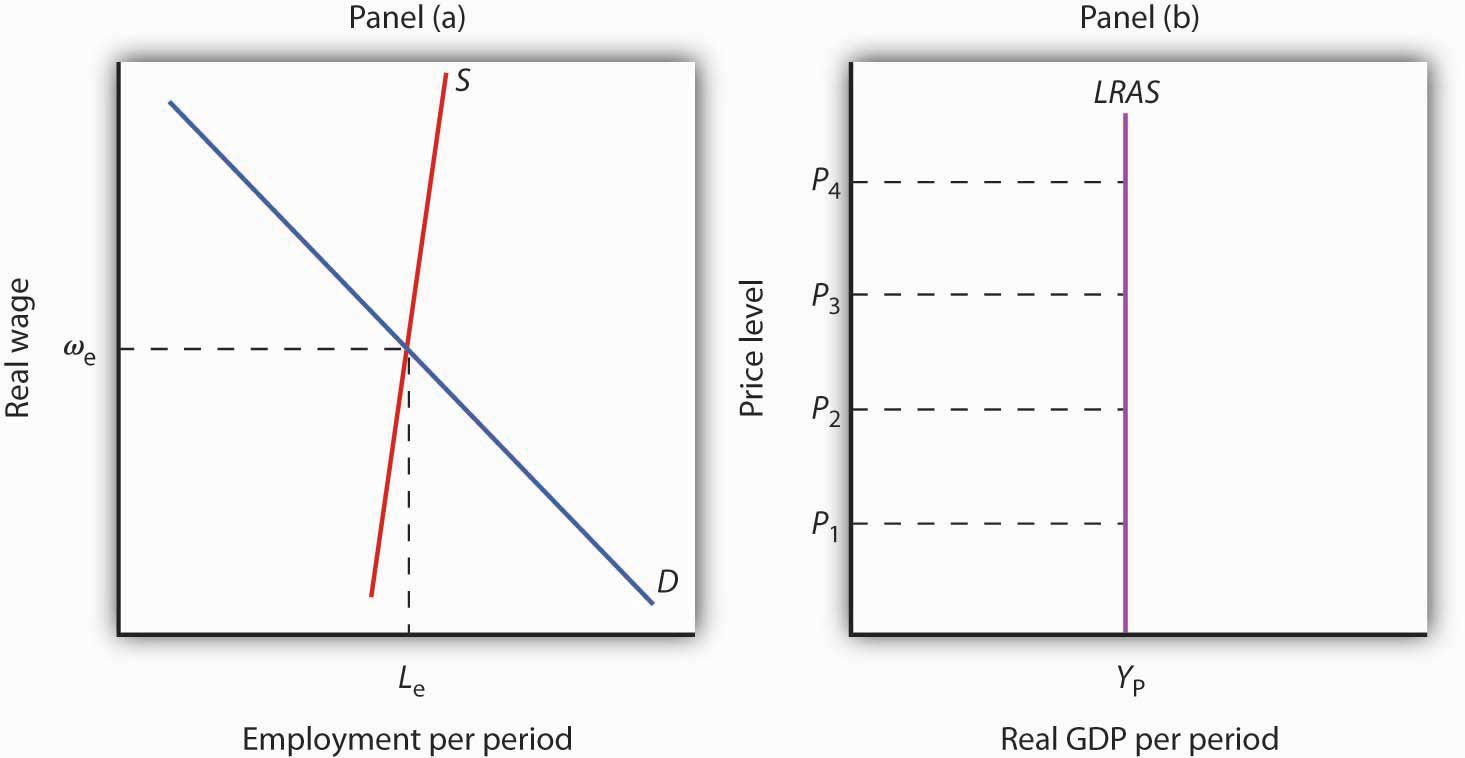

The long-run aggregate supply (LRAS) curve relates the level of output produced by firms to the price level in the long run. In Console (b) of Figure 22.five "Natural Employment and Long-Run Amass Supply", the long-run aggregate supply curve is a vertical line at the economy's potential level of output. There is a single real wage at which employment reaches its natural level. In Panel (a) of Figure 22.5 "Natural Employment and Long-Run Amass Supply", but a real wage of ωdue east generates natural employment L e. The economy could, however, achieve this real wage with any of an infinitely large set of nominal wage and price-level combinations. Suppose, for example, that the equilibrium real wage (the ratio of wages to the price level) is ane.5. Nosotros could have that with a nominal wage level of 1.five and a price level of one.0, a nominal wage level of 1.65 and a cost level of one.1, a nominal wage level of 3.0 and a price level of ii.0, then on.

Effigy 22.5 Natural Employment and Long-Run Aggregate Supply

When the economy achieves its natural level of employment, as shown in Panel (a) at the intersection of the demand and supply curves for labor, it achieves its potential output, as shown in Panel (b) by the vertical long-run aggregate supply curve LRAS at Y P.

In Panel (b) we run into cost levels ranging from P 1 to P 4. Higher cost levels would require higher nominal wages to create a real wage of ωeast, and flexible nominal wages would achieve that in the long run.

In the long run, then, the economic system tin achieve its natural level of employment and potential output at any price level. This determination gives u.s. our long-run amass supply bend. With only ane level of output at any price level, the long-run amass supply bend is a vertical line at the economy'south potential level of output of Y P.

Equilibrium Levels of Price and Output in the Long Run

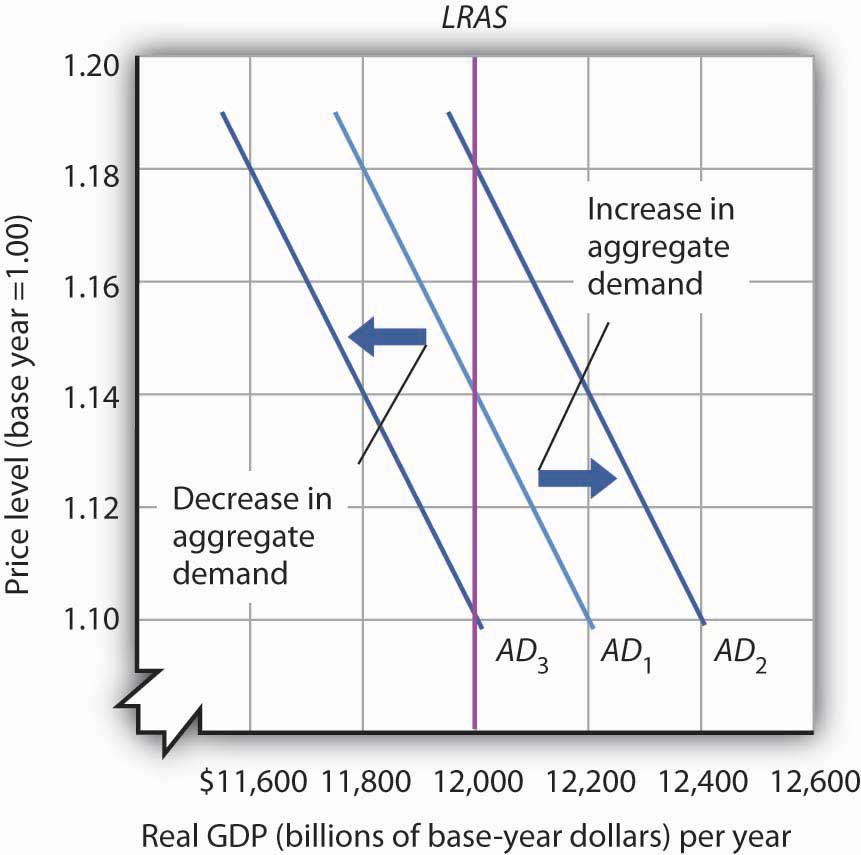

The intersection of the economic system's aggregate demand curve and the long-run aggregate supply curve determines its equilibrium real GDP and cost level in the long run. Effigy 22.6 "Long-Run Equilibrium" depicts an economy in long-run equilibrium. With amass demand at AD 1 and the long-run amass supply curve as shown, existent GDP is $12,000 billion per year and the toll level is 1.14. If aggregate demand increases to AD two, long-run equilibrium will be reestablished at real Gross domestic product of $12,000 billion per year, but at a higher price level of i.18. If amass demand decreases to Ad iii, long-run equilibrium will still be at real GDP of $12,000 billion per year, but with the now lower price level of 1.ten.

Figure 22.half dozen Long-Run Equilibrium

Long-run equilibrium occurs at the intersection of the aggregate need curve and the long-run aggregate supply bend. For the three amass demand curves shown, long-run equilibrium occurs at three different price levels, but ever at an output level of $12,000 billion per yr, which corresponds to potential output.

The Short Run

Analysis of the macroeconomy in the curt run—a period in which stickiness of wages and prices may preclude the economic system from operating at potential output—helps explain how deviations of real GDP from potential output can and do occur. Nosotros will explore the effects of changes in aggregate demand and in short-run aggregate supply in this section.

Brusk-Run Aggregate Supply

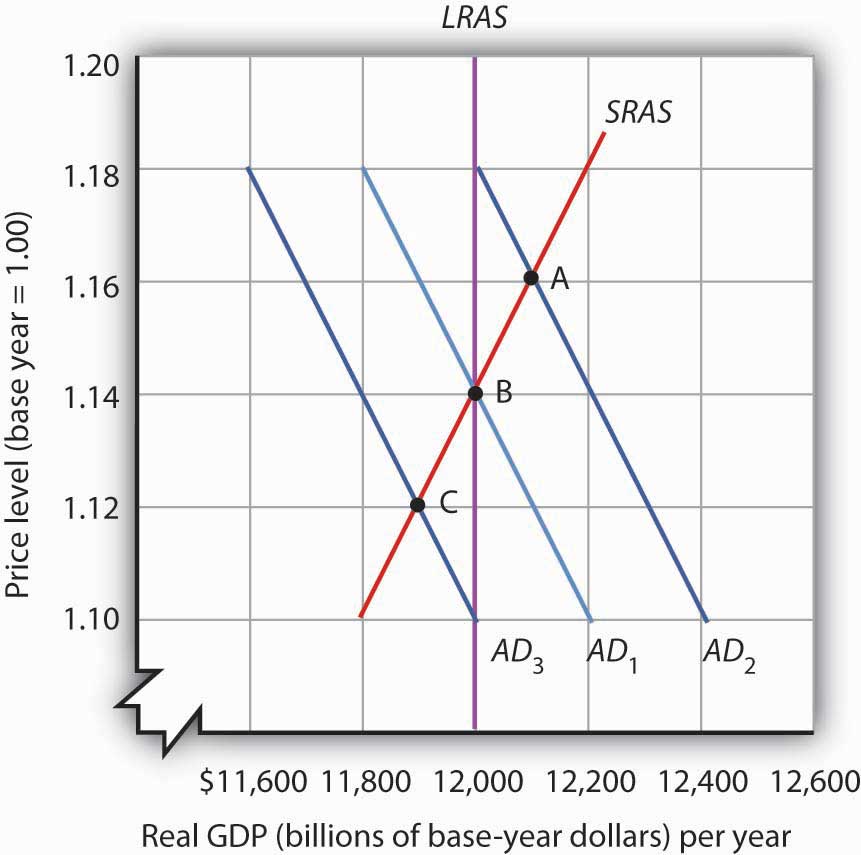

Figure 22.7 Deriving the Short-Run Aggregate Supply Bend

The economy shown here is in long-run equilibrium at the intersection of Advertizing ane with the long-run aggregate supply bend. If aggregate demand increases to Advertizing 2, in the short run, both existent GDP and the price level ascent. If aggregate demand decreases to AD iii, in the short run, both existent GDP and the price level fall. A line drawn through points A, B, and C traces out the short-run aggregate supply curve SRAS.

The model of amass demand and long-run aggregate supply predicts that the economy will eventually move toward its potential output. To see how nominal wage and price stickiness tin cause real GDP to be either above or below potential in the brusque run, consider the response of the economy to a change in aggregate demand. Figure 22.vii "Deriving the Short-Run Amass Supply Curve" shows an economy that has been operating at potential output of $12,000 billion and a price level of 1.14. This occurs at the intersection of AD 1 with the long-run aggregate supply bend at point B. At present suppose that the aggregate demand bend shifts to the correct (to Advertising 2). This could occur as a upshot of an increase in exports. (The shift from AD one to Advertising 2 includes the multiplied upshot of the increase in exports.) At the price level of one.14, at that place is now excess need and pressure on prices to rise. If all prices in the economy adapted quickly, the economic system would quickly settle at potential output of $12,000 billion, but at a college price level (1.eighteen in this case).

Is information technology possible to expand output higher up potential? Yes. Information technology may be the case, for case, that some people who were in the labor force simply were frictionally or structurally unemployed find work because of the ease of getting jobs at the going nominal wage in such an environment. The result is an economic system operating at signal A in Figure 22.seven "Deriving the Brusk-Run Aggregate Supply Bend" at a higher toll level and with output temporarily above potential.

Consider next the effect of a reduction in aggregate demand (to Advertisement 3), possibly due to a reduction in investment. Every bit the price level starts to fall, output as well falls. The economic system finds itself at a price level–output combination at which existent Gdp is below potential, at signal C. Again, price stickiness is to blame. The prices firms receive are falling with the reduction in demand. Without corresponding reductions in nominal wages, there will exist an increase in the real wage. Firms will utilise less labor and produce less output.

By examining what happens as aggregate need shifts over a menstruation when price adjustment is incomplete, nosotros can trace out the short-run amass supply bend by cartoon a line through points A, B, and C. The short-run amass supply (SRAS) bend is a graphical representation of the relationship between production and the price level in the short run. Amid the factors held abiding in drawing a short-run aggregate supply curve are the upper-case letter stock, the stock of natural resources, the level of engineering, and the prices of factors of production.

A alter in the price level produces a change in the amass quantity of goods and services supplied and is illustrated by the motion along the short-run aggregate supply bend. This occurs between points A, B, and C in Figure 22.vii "Deriving the Short-Run Aggregate Supply Bend".

A change in the quantity of goods and services supplied at every price level in the short run is a change in short-run amass supply. Changes in the factors held constant in drawing the brusque-run aggregate supply curve shift the curve. (These factors may too shift the long-run aggregate supply bend; we volition discuss them forth with other determinants of long-run aggregate supply in the side by side chapter.)

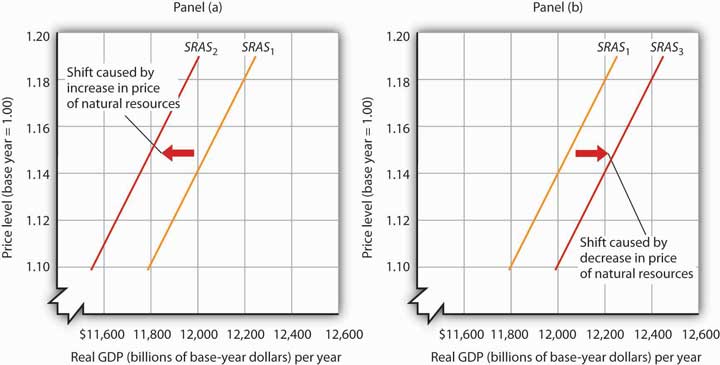

1 type of event that would shift the short-run amass supply bend is an increment in the price of a natural resources such as oil. An increase in the price of natural resource or any other factor of production, all other things unchanged, raises the price of production and leads to a reduction in short-run amass supply. In Panel (a) of Figure 22.eight "Changes in Brusque-Run Amass Supply", SRAS ane shifts leftward to SRAS ii. A decrease in the toll of a natural resource would lower the cost of production and, other things unchanged, would permit greater production from the economy's stock of resource and would shift the short-run aggregate supply curve to the correct; such a shift is shown in Panel (b) past a shift from SRAS 1 to SRAS 3.

Figure 22.8 Changes in Short-Run Aggregate Supply

A reduction in brusque-run aggregate supply shifts the curve from SRAS 1 to SRAS 2 in Panel (a). An increase shifts it to the right to SRAS 3, equally shown in Console (b).

Reasons for Wage and Cost Stickiness

Wage or price stickiness means that the economy may non always be operating at potential. Rather, the economy may operate either above or below potential output in the short run. Correspondingly, the overall unemployment rate will be beneath or in a higher place the natural level.

Many prices observed throughout the economy practise arrange speedily to changes in market place weather condition so that equilibrium, in one case lost, is speedily regained. Prices for fresh nutrient and shares of mutual stock are two such examples.

Other prices, though, adapt more slowly. Nominal wages, the price of labor, accommodate very slowly. We volition first await at why nominal wages are sticky, due to their association with the unemployment rate, a variable of great interest in macroeconomics, and then at other prices that may be viscous.

Wage Stickiness

Wage contracts set nominal wages for the life of the contract. The length of wage contracts varies from one calendar week or one month for temporary employees, to i twelvemonth (teachers and professors often have such contracts), to three years (for nearly union workers employed under major collective bargaining agreements). The existence of such explicit contracts means that both workers and firms accept some wage at the time of negotiating, even though economical atmospheric condition could alter while the agreement is nevertheless in force.

Call up well-nigh your ain job or a job you lot once had. Chances are yous go to work each mean solar day knowing what your wage will exist. Your wage does not fluctuate from one day to the adjacent with changes in need or supply. Y'all may have a formal contract with your employer that specifies what your wage volition be over some period. Or you may have an breezy understanding that sets your wage. Any the nature of your understanding, your wage is "stuck" over the period of the agreement. Your wage is an example of a viscous price.

One reason workers and firms may be willing to accept long-term nominal wage contracts is that negotiating a contract is a costly process. Both parties must continue themselves adequately informed about market place conditions. Where unions are involved, wage negotiations raise the possibility of a labor strike, an eventuality that firms may prepare for by accumulating additional inventories, also a plush process. Even when unions are non involved, time and energy spent discussing wages takes away from time and energy spent producing goods and services. In improver, workers may just adopt knowing that their nominal wage will be fixed for some flow of time.

Some contracts do attempt to have into account changing economical conditions, such as inflation, through cost-of-living adjustments, just fifty-fifty these relatively elementary contingencies are not every bit widespread as ane might think. One reason might be that a house is concerned that while the amass price level is rising, the prices for the goods and services it sells might not be moving at the same rate. Also, cost-of-living or other contingencies add complexity to contracts that both sides may want to avoid.

Even markets where workers are not employed under explicit contracts seem to comport as if such contracts existed. In these cases, wage stickiness may stem from a desire to avoid the same uncertainty and adjustment costs that explicit contracts avert.

Finally, minimum wage laws foreclose wages from falling below a legal minimum, even if unemployment is rising. Unskilled workers are specially vulnerable to shifts in amass demand.

Price Stickiness

Rigidity of other prices becomes easier to explain in lite of the arguments nearly nominal wage stickiness. Since wages are a major component of the overall toll of doing business, wage stickiness may lead to output price stickiness. With nominal wages stable, at least some firms can adopt a "wait and come across" attitude before adjusting their prices. During this time, they can evaluate information about why sales are rising or falling (Is the change in need temporary or permanent?) and try to assess probable reactions by consumers or competing firms in the industry to whatsoever price changes they might make (Will consumers be angered by a cost increase, for case? Will competing firms match price changes?).

In the meantime, firms may prefer to suit output and employment in response to changing market conditions, leaving product toll lonely. Quantity adjustments have costs, simply firms may assume that the associated risks are smaller than those associated with toll adjustments.

Some other possible explanation for toll stickiness is the notion that in that location are adjustment costs associated with changing prices. In some cases, firms must impress new price lists and catalogs, and notify customers of price changes. Doing this too often could jeopardize customer relations.

Yet another explanation of price stickiness is that firms may have explicit long-term contracts to sell their products to other firms at specified prices. For case, electric utilities often buy their inputs of coal or oil under long-term contracts.

Taken together, these reasons for wage and price stickiness explicate why amass toll adjustment may be incomplete in the sense that the change in the price level is insufficient to maintain existent Gross domestic product at its potential level. These reasons practise not atomic number 82 to the conclusion that no price adjustments occur. But the adjustments crave some time. During this time, the economy may remain above or below its potential level of output.

Equilibrium Levels of Toll and Output in the Short Run

To illustrate how we will apply the model of aggregate need and aggregate supply, let us examine the touch on of two events: an increase in the cost of health care and an increment in government purchases. The first reduces curt-run aggregate supply; the second increases aggregate need. Both events change equilibrium real GDP and the price level in the short run.

A Change in the Cost of Health Care

In the U.s.a., most people receive health insurance for themselves and their families through their employers. In fact, information technology is quite common for employers to pay a big pct of employees' wellness insurance premiums, and this benefit is often written into labor contracts. Every bit the cost of health intendance has gone upwardly over fourth dimension, firms have had to pay higher and higher health insurance premiums. With nominal wages fixed in the short run, an increase in health insurance premiums paid past firms raises the cost of employing each worker. It affects the cost of product in the aforementioned way that higher wages would. The result of higher wellness insurance premiums is that firms will choose to employ fewer workers.

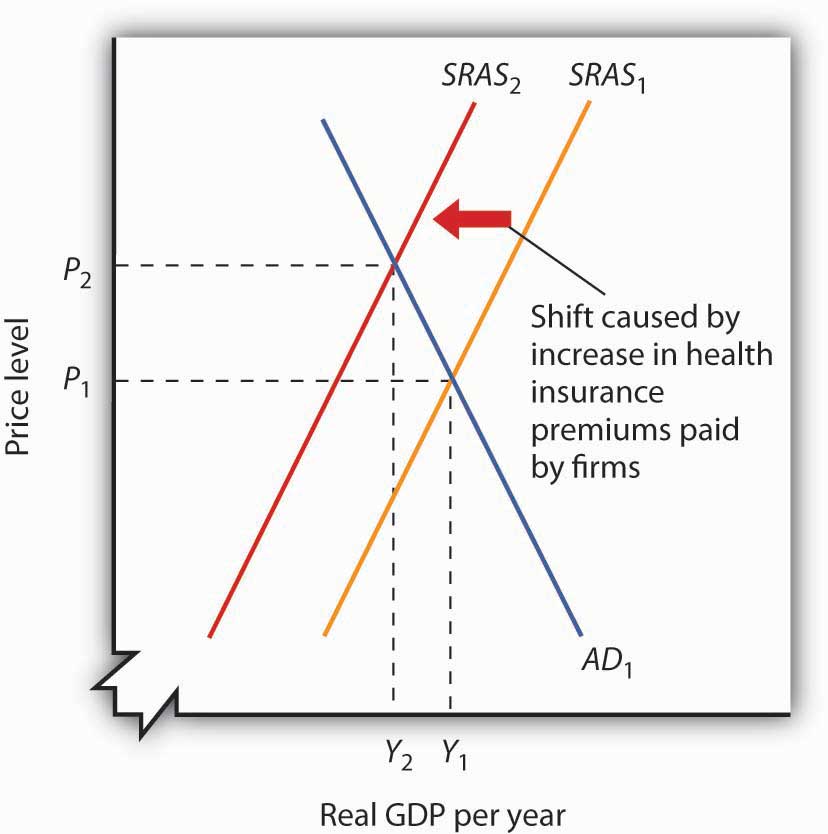

Suppose the economy is operating initially at the brusque-run equilibrium at the intersection of Advert 1 and SRAS 1, with a real Gdp of Y one and a price level of P 1, as shown in Effigy 22.nine "An Increase in Health Insurance Premiums Paid past Firms". This is the initial equilibrium price and output in the curt run. The increment in labor cost shifts the brusk-run amass supply curve to SRAS ii. The price level rises to P ii and existent Gross domestic product falls to Y 2.

Figure 22.9 An Increment in Wellness Insurance Premiums Paid by Firms

An increase in health insurance premiums paid past firms increases labor costs, reducing short-run aggregate supply from SRAS one to SRAS 2. The price level rises from P i to P ii and output falls from Y 1 to Y two.

A reduction in health insurance premiums would have the contrary effect. There would exist a shift to the right in the short-run aggregate supply bend with pressure on the price level to autumn and real GDP to rise.

A Change in Government Purchases

Suppose the federal regime increases its spending for highway construction. This circumstance leads to an increase in U.Due south. regime purchases and an increase in amass demand.

Assuming no other changes impact aggregate demand, the increase in government purchases shifts the amass demand curve past a multiplied amount of the initial increment in government purchases to AD 2 in Figure 22.10 "An Increment in Authorities Purchases". Real Gross domestic product rises from Y 1 to Y 2, while the price level rises from P i to P ii. Detect that the increment in real Gdp is less than it would have been if the toll level had not risen.

Figure 22.10 An Increase in Authorities Purchases

An increase in government purchases boosts amass demand from Advertisement 1 to Advertisement ii. Short-run equilibrium is at the intersection of Advertizing 2 and the curt-run aggregate supply curve SRAS i. The cost level rises to P 2 and existent GDP rises to Y ii.

In contrast, a reduction in government purchases would reduce aggregate need. The aggregate demand bend shifts to the left, putting pressure on both the toll level and real Gdp to fall.

In the short run, existent GDP and the toll level are adamant by the intersection of the aggregate demand and brusque-run aggregate supply curves. Think, however, that the brusque run is a flow in which sticky prices may prevent the economic system from reaching its natural level of employment and potential output. In the next department, we will encounter how the model adjusts to move the economy to long-run equilibrium and what, if anything, can be done to steer the economy toward the natural level of employment and potential output.

Key Takeaways

- The curt run in macroeconomics is a flow in which wages and some other prices are viscous. The long run is a period in which full wage and price flexibility, and market adjustment, has been accomplished, so that the economy is at the natural level of employment and potential output.

- The long-run aggregate supply bend is a vertical line at the potential level of output. The intersection of the economy's aggregate need and long-run amass supply curves determines its equilibrium real GDP and price level in the long run.

- The short-run aggregate supply curve is an upwardly-sloping curve that shows the quantity of total output that will exist produced at each cost level in the brusk run. Wage and toll stickiness account for the short-run amass supply curve's upwardly slope.

- Changes in prices of factors of product shift the short-run amass supply curve. In addition, changes in the capital stock, the stock of natural resources, and the level of applied science can also cause the brusk-run amass supply curve to shift.

- In the brusk run, the equilibrium price level and the equilibrium level of full output are determined by the intersection of the aggregate demand and the short-run aggregate supply curves. In the curt run, output can be either below or above potential output.

Try Information technology!

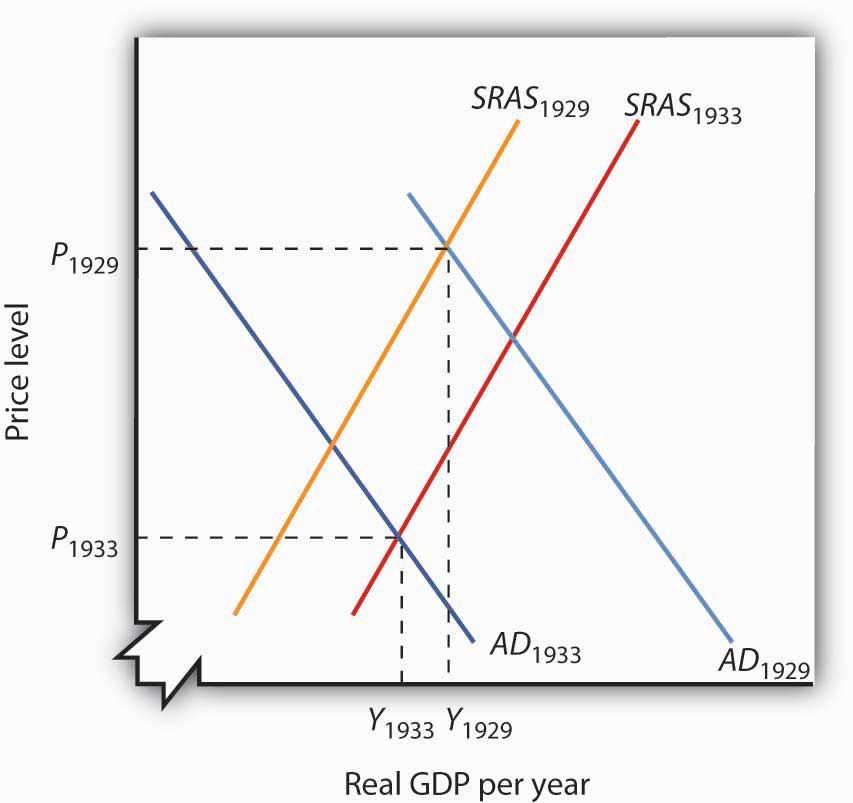

The tools nosotros have covered in this section can be used to sympathize the Dandy Depression of the 1930s. We know that investment and consumption began falling in late 1929. The reductions were reinforced past plunges in net exports and government purchases over the next four years. In add-on, nominal wages plunged 26% between 1929 and 1933. Nosotros also know that real Gdp in 1933 was thirty% below real GDP in 1929. Utilize the tools of aggregate demand and short-run aggregate supply to graph and explain what happened to the economy betwixt 1929 and 1933.

Example in Point: The U.S. Recession of 2001

Figure 22.11

Simon Cunningham – Recession – CC Past 2.0.

What were the causes of the U.Due south. recession of 2001? Economist Kevin Kliesen of the Federal Reserve Depository financial institution of St. Louis points to four factors that, taken together, shifted the aggregate demand curve to the left and kept it there for a long enough menses to go along existent Gross domestic product falling for about nine months. They were the fall in stock market prices, the decrease in business investment both for computers and software and in structures, the turn down in the real value of exports, and the backwash of nine/11. Notable exceptions to this list of culprits were the beliefs of consumer spending during the period and new residential housing, which falls into the investment category.

During the expansion in the late 1990s, a surging stock market probably made it easier for firms to raise funding for investment in both structures and data technology. Fifty-fifty though the stock market chimera burst well before the bodily recession, the continuation of projects already underway delayed the decline in the investment component of GDP. Besides, spending for it was probably prolonged as firms dealt with Y2K computing problems, that is, calculator problems associated with the alter in the date from 1999 to 2000. Most computers used only two digits to indicate the year, and when the year changed from '99 to '00, computers did non know how to interpret the change, and extensive reprogramming of computers was required.

Real exports vicious during the recession because (1) the dollar was strong during the period and (2) real Gross domestic product growth in the rest of the world fell almost 5% from 2000 to 2001.

Then, the terrorist attacks of nine/11, which literally shut downwards transportation and financial markets for several days, may have prolonged these negative tendencies just long enough to turn what might otherwise have been a mild decline into enough of a downtown to authorize the catamenia equally a recession.

During this period the measured price level was essentially stable—with the implicit price deflator rising by less than 1%. Thus, while the amass demand bend shifted left as a result of all the reasons given above, at that place was besides a leftward shift in the short-run aggregate supply curve.

Source: Kevin L. Kliesen, "The 2001 Recession: How Was Information technology Dissimilar and What Developments May Take Caused It?" The Federal Reserve Depository financial institution of St. Louis Review, September/October 2003: 23–37.

Respond to Try It! Trouble

All components of aggregate demand (consumption, investment, government purchases, and net exports) declined between 1929 and 1933. Thus the amass need curve shifted markedly to the left, moving from Advertisement 1929 to AD 1933. The reduction in nominal wages corresponds to an increase in short-run aggregate supply from SRAS 1929 to SRAS 1933. Since real Gross domestic product in 1933 was less than real GDP in 1929, we know that the movement in the aggregate demand bend was greater than that of the short-run amass supply curve.

Figure 22.12

Source: https://open.lib.umn.edu/principleseconomics/chapter/22-2-aggregate-demand-and-aggregate-supply-the-long-run-and-the-short-run/

Posted by: parrottnowed1944.blogspot.com

0 Response to "What Is The Relationship Between Nominal Money Supply And The Price Level In The Long Run"

Post a Comment